Steve The Manager left Camelot Music for a bigger store down in Florida. Our new boss was a 24 year-old named Rich who sported cowboy boots and a poodle mullet. Almost immediately he fired Alex, Steve’s right-hand man and the guy who got me my job, and brought in his own assistant manager.

Rich was a creep in the most literal sense of that word — he crept. Spotting his bleached blond curly perm lurking across the mall was our live-action version of Where’s Waldo. Or he’d sneak in through the back door and hide in his darkened office, peeking at us through the two-way mirror at the back of the store. Sometimes he’d pretend to go out of town in hopes of catching us fucking off, which he did.

“Come on, Rich, you know people are going to slack off when you aren’t here,” I said.

“No, I don’t know that. When I’m not here I expect everyone to work harder.”

“Seriously? You’ve been an employee, right?”

“Yes, seriously. I always worked harder when my manager was away.”

Probably because your head wasn’t wedged in his ass.

That was the downside of having Mr. Super Team for a boss, but there was an upside, too. Because Mullethead thought he was the greatest manager in history, he felt the need to impart his year of wisdom upon the rest of us. This meant new responsibilities for even the underest of the underlings. I got the 45 wall.

For most of its history the music business revolved around the single, sometimes at 45 RPM, sometimes 78, and prior to flash memory at 7,200 revolutions per minute. Go back to the era of the Victrola and the Edison phonograph — 10″ platters with a song on either side. Go back farther still to wax cylinders and player piano rolls, music boxes and sheet music. One song per customer, two tops. Even early albums were mostly collections of singles with a little bit of filler.

That changed in the mid-sixties. I’m supposed to say here that Pet Sounds and Sgt. Pepper were the turning points, and in a Biblical “begat” way that’s true. But in market terms Sgt. Pepper stands alone as the game changer.

Pet Sounds is a brilliant album, but to this day the majority of people think of the Beach Boys as a singles band. Here’s what I mean: Ask somebody what they think of the Beach Boys and the safe money bet is that they’ll talk about songs. Repeat the same experiment with The Beatles and my guess is that most of the conversations will center on albums: I love The White Album; Sgt. Pepper is amazing, that kind of thing.

From 1967 it was all about the album. Songs were still important, but now as part of a cohesive whole. Singles were no longer the point – they were just the marketing collateral that led buyers to the album.

There were exceptions, of course. Michael Jackson and Quincy Jones designed Thriller around the idea of an album comprised of nothing but singles, and the end result was the biggest selling album of all time. I argue that this success was attributable directly to the fact that singles were the “commercial” for Thriller, and since the album was all singles it had one commercial after another in heavy radio rotation for a full year. Def Leppard picked up on this idea and did the same thing with Hysteria, which I hated every bit as much as Thriller.

The album bubble lasted a good thirty-five years or so, until the MP3 in general and iTunes in particular monkey stomped it. The whole package — the cover art, lyric sheets, inner sleeves and liner notes; the thoughtful sequencing of the song cycle — none of it matters anymore. We’ve come full circle back to the single.

Well, we haven’t, the music industry has. Selling product is what that business is all about, and when they see one billion Youtube views for “Gangam Style” they see opportunity. It’s math, not art: If we can figure out how to get even a nickel per view…

Anyway, Rich the Mullethead decided that I was going to start doing 45 orders. We still sold a few singles in 1985, even if the lowly 45 was dominated by the mighty album at that time.

If you’ve ever worked in retail (or purchasing of any sort, probably) you know that the fundamentals of inventory control are fairly simple: I need enough product on hand to meet demand, but not so much that I’m needlessly tying up dollars or risking losses on returned stock.

Easy, right? If I sell 100 hamburgers a day, I better not have only 75 patties on-hand Wednesday or I’ll lose 25 sales. On the other hand, I better not buy 200 patties or 100 will spoil (Note: Does not apply to fast food. Plastic does not spoil).

But there are variables to consider: Is the company running ads? Is there something happening in the neighborhood this Wednesday that might change the 100 burger traffic pattern? Is mad cow disease in the news cycle again this week? Is a new restaurant opening down the street, or an old one closing?

On and on. Burgers, records, they’re both round and made of plastic. Rich taught me the tools of the singles trade: Read Billboard, call the local radio stations and ask for their playlists, and most importantly follow the tried and true formula for calculating reorder quantities. This last point was the eleventh commandment.

I took it all very seriously because unfortunately that’s what I do. Everything was input for my mission critical $3.50 an hour job — the radio, trade magazines, conversations I eavesdropped on around the mall. I was hellbent on being the greatest 45 orderer in Camelot Music history.

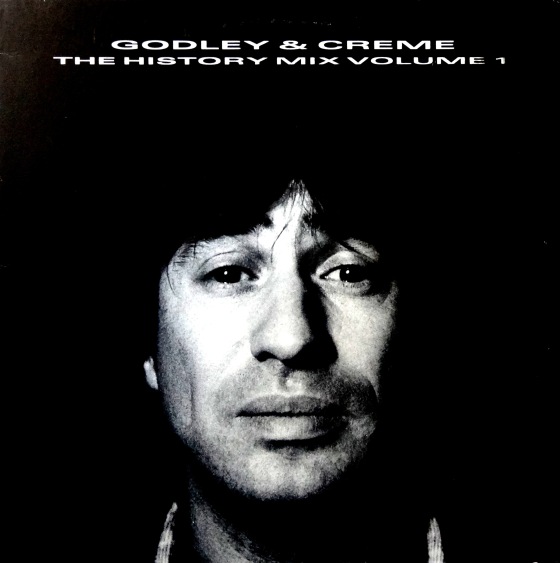

One afternoon while my girlfriend, Christie, and I were watching MTV I caught a black and white video composed entirely of close-ups of mopey faces that morphed into each other — a black woman became a white man became a little girl, etc. Nothing but close-ups of sad faces: no spandex cock rock guitar solos or zombie dance sequences.

And the song — the bleak, beautiful, depressing song with its doleful falsetto wail. The whole thing was striking.

A few days later Rich scrambled out from behind his two-way mirror, cowboy boots stomping their way toward me.

“What’s this?” he asked, and he pointed to his clipboard.

“That’s this week’s order.”

“No, this,” and he jabbed his girly finger at a specific line.

“New single. It’s great.”

“I checked Billboard. It isn’t in the Hot 100.”

“Nope.”

“And it’s not on any of the local radio stations’ playlists.”

“Not yet, but it will be. MTV is playing it.”

“That doesn’t mean it will sell.”

“It will. These guys used to be in 10CC.”

“So what? Who cares about 10CC?”

“You should see the video,” I said. “It’s so cool.”

Rich looked at me like I farted in his individual pudding cup. “You can’t buy a single for the store because the video is cool. That’s not how it works.”

“Rich, I ordered five copies. I really don’t think Camelot Music is going to go broke if I’m wrong.”

“That’s exactly why record stores go broke, because employees buy what they like, not what sells.”

“If they don’t sell I’ll buy them, okay?”

He stomped back to his office, his Greatest American Hero mullet bobbing with each step.

The next week we sold all five copies of Godley & Creme’s “Cry,” and then it went into heavy rotation on MTV and we were selling dozens every week. The single eventually peaked at number 16 on Billboard’s Hot 100 US singles chart. Not too shabby.

The last I heard Rich was working for a record label, and record labels were in decline. I’m not saying that Rich caused the downfall of the music industry. That would be silly.

No, I’m saying that tens of thousands of Riches killed the music industry with their tried and true formulas, their lack of imagination, and their aversion to change.

Also, I got lucky on the Godley & Creme thing. I didn’t know what the hell I was doing, but Rich doesn’t need to know that so let’s keep that nugget between you and me.

Coda: I wrote this story in a coffee shop. When I finished and fired up my car, “A Day In the Life” was on the radio. The greatest song The Beatles ever recorded was never released as a single, yet 45 years later it is still in radio rotation. Do you think that the same can be said for “Gangam Style,” the most popular clip in Youtube history?

Moral for music executives: You can sell the hell out of one shitty song for six months, or you can sell one brilliant song for 45 years. Which is the better investment?

Leave a reply to James Stafford