Friday evening, November 17, 1975, Chicago suburbs.

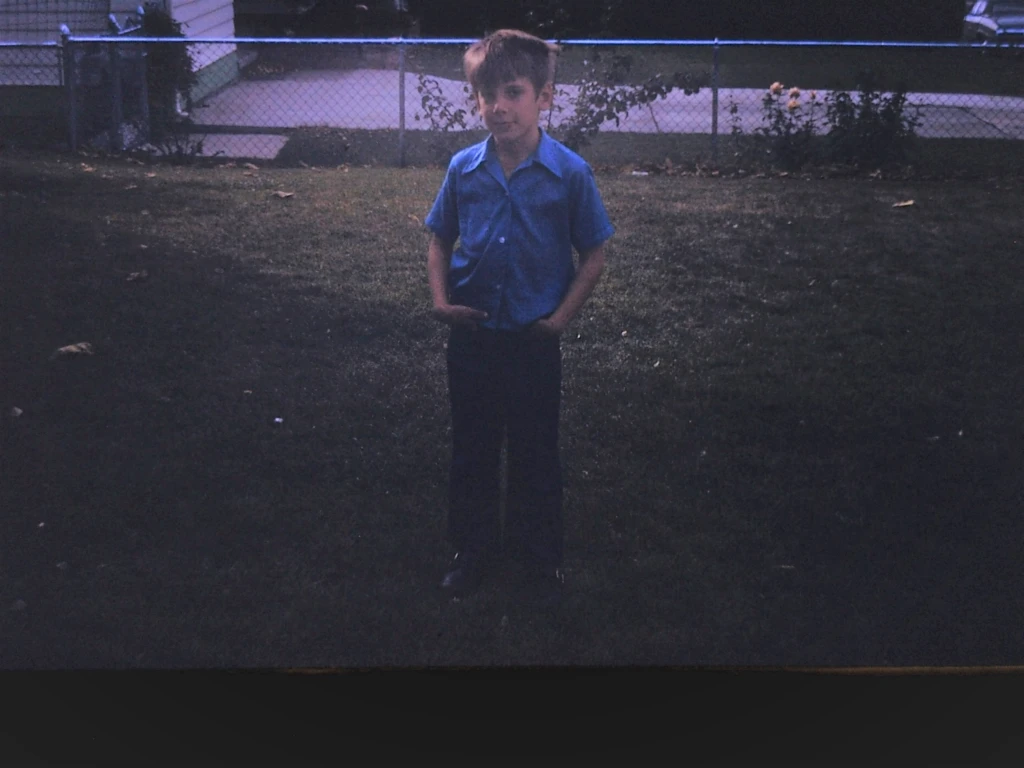

It’s dark and cold. We’ve just finished dinner and my father is loading our old emerald-green Bel Air station wagon. I try to help, but my parents’ hard shell suitcase is half the height and twice the weight of an eight year-old boy. “Why are we doing this?” I ask.

“Doing what, loading the car? You want to wear the same clothes for a week, dumbbell?” He heaves the big powder blue suitcase into the “back in the back,” as my sisters and I call the station wagon’s cargo area.

“No, I mean why are we doing this right now?”

“So we can get an early start. It’s a long drive to Colorado, and this new goddamned 55 speed limit is going to make it even longer.”

He shoves in the last of the luggage–my little suitcase, my mother’s makeup case–and then tosses in an old blanket. “What’s that for?” I ask.

“You never know,” he says.

Saturday morning three a.m., November 18.

Our parents herd their three groggy children into the back seat of the Bel Air, where we arrange ourselves into upright sleeping postures emphasizing a lack of physical contact with each other. Two of us lean against our car doors like red-eye airline passengers while our long suffering middle sibling sits in the center of the slippery vinyl bench seat, feet resting atop the transmission tunnel, trying her best not to flop over in her sleep. An observer might think they we each carried some highly transmissible disease like polio. Or cooties.

Up front, our folks don’t speak. Periodically the brrrap brrrap brrrap of tires on the road’s shoulder wakes me up, or maybe it’s the jerk of the big car fighting its way back into the freeway’s calm current, luggage rattling around immediately behind me. These episodes are punctuate by my bug-eyed, blinking father taking a few deep breaths before assuring my mother that he’s fine, fine, no need to pull over.

The sun looms low on the horizon behind us when I finally awake for good. One of my sisters reads a Little House on the Prairie book, the eldest crochets a granny square. My parents listen to an old-timey radio show on a staticky AM station that fades in and out. I grab the book that I borrowed from my grade school’s library, The Wright Brothers by Quentin Reynolds, and begin reading. This is probably my tenth pass on this particular book: The sign-out card tucked into the pocket is one long row of carefully drafted Jimmy Stafford signatures.

“I have an idea,” our big sister announces. “Let’s take turns on the seat. Two of us sit on the floor so that the other one can stretch out on the seat. I’ll go first.” Middle sister and I wedge ourselves into our respective footwells with our books and the eldest stretches above us like Cleopatra on an emerald green litter.

Ten minutes pass, twenty, thirty. Our turns on the seat never arrive. “Can I go to the back in the back?” I shout from my hole.

“Whatever floats your boat,”my father replies. I crawl over my big sister, making sure to step on her a couple of times for good, spiteful measure, and squeeze in to the gap separating the luggage from the station wagon’s tailgate. This is luxury travel, my own little reading nook with no risk of sister cooties.

Added bonus: I’m face to face with the long haul drivers who sneak up on our back door in their cab-over Petes with their reefers on and their Jimmys hauling hogs. C.W. McCall’s “Convoy” is the big hit on WLS Chicago, John “Records” Landecker spinning it what seems like every third song. McCall’s truckers are playground heroes at school, as is any kid who can recite the song’s lyrics without error. My school buddies assured me that if I raise my fist and pull downward, like a cartoon engineer blowing his train whistle, truckers will reply with a blast from their air horns. I do this for mile after mile from my hiding place behind the luggage until my father screams, “What the hell is wrong with these goddamned truckers? I’m driving five over the goddamned speed limit!”

“I have to go the bathroom,” my sister cries from her dark hole in the footwell.

“We still have a quarter tank of gas,” our father shouts over the third straight episode of The Shadow. (What lurks in the hearts of men? The Shadow knows: Making good time.)

“But I have to go.”

“If I stopped every time one of you said you had to go we wouldn’t get to Colorado until Christmas,” he replies, and then to my mother: “Give her a cookie.” Mom retrieves her box of off-brand, expired, outlet store cookies from the floorboard and hands one between the seats. This conversation repeats all the way across Iowa, Nebraska, and eastern Colorado. To this day my siblings and I wonder at the correlation between full bladders and bargain-priced sugary baked goods.

Our bladders distorted and our pancreases inflamed, we pull into the driveway of my father’s parents’ home around eight p.m. mountain time. Grandpa stands in front of his Buick, a copper-colored ’72 Riviera, smoking an unfiltered Raleigh and drinking a Coors. Grandma exits the little mountain cabin and joins him. They stand like two subjects in a Grant Wood painting as we bail out of the Bel Air. “How was the drive?” Grandpa asks as he shakes my dad’s hand.

“Your father said that old car wouldn’t make it all the way from Illinois,” Grandma adds.

“Mable, I never said no such a goddamn thing.”

Grandma quickly retreats and looks for another opening in her ongoing campaign to convince my father to move back to Colorado. “Must be hard on those kids, being in the car so long.”

Their home is an old hunting cabin with a couple of bedrooms, kitchen, and bathroom tacked on the back. The original cabin is divided into living and dining rooms separated by a half wall topped with three fish tanks, each holding a piranha. The living room reflects my grandfather’s eccentric tastes: flea market tapestries featuring matadors and poker playing dogs; a battery-powered figurine of a cherubic little boy who urinates bourbon at the touch of a button; a chain of Coors pull tabs that circle the room like crown moulding; a gun rack holding his old Army issue M1 rifle, and next to that a mounted deer head. “Where’d that come from?” my sister asks, motioning toward the glass-eyed buck.

Grandpa taps his cigarette over the nearest ashtray. “That feller was running down the hill and got going so fast he couldn’t stop. When he hit the house his head shot straight through the goddamned wall. You can go outside in the morning and see the rest of him.”

“They’re building new houses over in Conifer,” Grandma says. “Big houses. They say they’re pretty cheap.”

“You got another one of those beers, Dad?” my father asks, avoiding the topic. The question perks our little ears: Our father doesn’t drink. Grandpa disappears into the kitchen while Grandma continues her soft sell of affordable local real estate. He returns with two fresh cans of Coors–one for my father and another one for himself–and interrupts her sales pitch. “Your sister got a job at the plant down in Golden. She gets five goddamned cases free every week.”

“Oh yeah?” Dad says. “I’ll have to talk to her about that. When are they coming over?”

“You hear the one about the boy who found a magic lamp?” Grandpa replies. “The genie says ‘I’ll give you one wish,’ and the boy thinks for a minute and says ‘Well I reckon I want to be covered with hair head to toe.’ ‘Why the hell you want to be covered with hair’ the genie says and the boy says ‘Well my sister’s got a patch of hair about this big and the boys pay her a quarter just to look at it. Imagine how much money I can make.’”

The two men laugh while the rest of us stare into infinity like the deer who ran through the wall. “We should probably get these kids to bed,” my mother says. “It’s been a long day.”

“I call couch,” my oldest sister says.

“Air mattress,” adds my other sister. For the next week I’ll sleep on a war surplus army cot, tossing and turning beneath a matching scratchy wool blanket, illuminated by the soft glow of bubbling tanks filled with killer fish.

And every morning around 5 a.m. my grandmother will bang every pot against every pan she owns, this under the guise of cooking my grandfather’s breakfast of fried eggs and bacon. He sits at the end of the dining room table, just a few feet away from me on the other side of the piranha wall, smoking the first Raleigh of the day while sipping coffee from a chocolate brown ceramic mug. “Are those kids up yet” she shouts over the clanging cookware. “They must let those kids sleep the whole day away.” My grandfather ignores her.

When we finally surrender and join Grandpa at the table, Grandma sets out bowls, spoons, and Kellogg’s variety packs–shrink wrapped assortments of sugary cereals packaged in miniature versions of the big, colorful boxes lining our grocery store’s shelves. All the fun-sized hits are present: Froot Loops, Apple Jacks, Lucky Charms, Frosted Flakes, Sugar Pops, Rice Krispies, each featuring eight essential vitamins and nutrients along with enough sugar to throw an adult rhino into a diabetic coma. My teeth ache just looking at the packaging, but I can’t wait to dig in. She sets a quart-sized carton in the middle of the table. “You’ll have to use cream. Your grandpa forgot to get milk.”

“That’s a goddamned lie,” Grandpa fires back. “You didn’t ask me to pick up any goddamned milk. What the hell’s a matter with you, woman?”

“Oh, I know it,” she says, and she hustles back to the kitchen to flip the bacon, which at this point has been frying so long that each slice is the color of beef jerky and more fragile than a quail’s egg: look at a piece wrong and it crumbles into dust. To this day I’m not sure whether I’d pick sugary cereal with cream or crumbly bacon as my last meal, should that choice need to be made.

Neither, probably, as what kept hope alive during 1,000 miles of off-brand Samsonite whacking me in the head was the knowledge that on Thanksgiving Day I’d be allowed to eat my weight in Grandma’s macaroni and cheese. Overall the woman’s cooking was a violation of the Geneva Convention, but her mac and cheese remains legendary, as my dying wish to be buried in a man-sized Corning Ware casserole with a blue cornflower stenciled on its side attests.

On paper her macaroni and cheese shouldn’t have worked. This was a recipe that would’ve caused the Galloping Gourmet to gallop right off your local PBS station and into another profession, that would’ve sent Julia Child straight back to the CIA. Grandma didn’t really make mac and cheese; rather, she simply threw the ingredients for that dish into a ceramic casserole dish and with the help of a 350 degree oven let them figure it out for themselves. She understood that unlike bickering siblings in the back seat of a station wagon, cheese, milk, butter and noodles actually want to intermingle.

We’ll fast forward through a few vacation days, as that’s really the best way to express the tedium of an eight year-old boy staring at pine cones, half watching Mutual of Omaha’s Wild Kingdom, listening to the whiz of Grandpa’s dirty punchlines fly past, and tossing and turning beneath an itchy army blanket until the five a.m. breakfast routine repeated. The only episode worth mentioning during those few days was an overheard conversation between my parents wherein they conspired to buy a new kind of turkey with a pop-up timer built right in so that my grandmother couldn’t “dry the damned thing out for once.”

And so we arrive at Thanksgiving Day, a holiday whose only non-mac and cheese high point for a third grader circa 1975 was the first annual appearance of Santa Claus. Santa always brought up the rear of the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade, which rendered listening to hosts Helen Reddy, Peter Marshall, and Ed McMahon banter for two hours about oversized balloons must-see TV. (“Here comes a giant mock-up of the little Cootie toy. The cutie on Cootie is well known child actor Mason Reese!”)

Somewhere around Mighty Mouse my Aunt Sissy and her family swing through the front door. Her two sons, both a bit younger than me, immediately join me in front of Grandpa’s television while their father, who my sisters and I secretly call Uncle Buddha due to his ample girth, flops into the nearest chair. Every joint–both Uncle Buddha’s and the chair’s–howls in protest as the mass of humanity settles in. “What’s this crap? Isn’t there a football game on? Change the channel,” he orders, and with the loud clunk of the TV dial moving to the next channel my time investment into a Santa sighting is negated. I won’t see Saint Nick until the annual Rankin-Bass TV specials air or my mother drives me to the shopping mall to sit on a total stranger’s lap, whichever comes first.

My father exchanges tense greetings with his sister, who mutters something that sounds like “it’s in the trunk” before asking how our drive was.

“Not bad,” Dad says. “We made good time.”

“That old Bel Air giving you any problems?” Uncle Buddha interjects from his suffering recliner. Somehow without moving he’s managed to acquire a Coors and a can of cocktail peanuts, the latter perched on his ample belly.

“Nope. It runs great as long as Dingbat doesn’t try to take it sailing.” This is intended as a joke, a call back both to my father’s favorite television character, Archie Bunker, and to the time my mother drove through a flooded intersection and damaged the car’s exhaust system.

“Giving women driver’s licenses is like giving monkeys shotguns,” Uncle Buddha mumbles through his peanut-stuffed mouth. I don’t know whether it’s the sight of his half-masticated food, the odors coming from kitchen where Grandma has been cooking since five a.m. (“are those kids still asleep?”), the cacophony of bickering cousins and a blaring football game, or my grandfather’s cigarette smoke, but my head aches and my stomach churns.

“You still working for the county?” my father asks.

“Oh yeah, easiest job I ever had,” Uncle Buddha brags.

“They still have that picture of you sleeping at your desk stuck up on the bulletin board?”

The heat in the little house creeps up into the mid-eighties. Some of that is the roaring fire that Grandpa regularly stokes, Coors in one hand and fireplace poker in the other, Raleigh dangling from his lips. The majority rolls in from the kitchen in humid waves, the result of pots of water boiling on all four stove eyes for no apparent reason and the poor Butterball giving up the last of its moisture after seven hours in the oven. Its little red “done” indicator popped up hours ago, sending Grandma on a jag about these worthless newfangled devices that don’t work properly. Hot and humid, but for whatever reason I’m the only one who seems uncomfortable.

My mother wanders in from the kitchen. Throughout the day she moves from room to room, a few minutes in the living room serving as the butt of my father’s cooking and driving jokes, then back to the kitchen where her offers to help her mother-in-law with the big holiday meal are ignored. “I don’t feel good,” I tell her. She rests the back of her hand on my forehead. It’s a pleasant feeling, not just due to the coolness of her skin but because my mama is caring for me.

“You’re a little feverish,” she says, and two little wrinkles appear between her eyebrows.

“There’s nothing wrong with him,” my aunt says. “The little brat just wants attention.”

“Why don’t you go lay down in the back bedroom,” my mother tells me. This is a treat even bigger than sugary cereal in tiny boxes. I’ve always been an army cot in the living room kid, and now I’ve gained admission to the inner sanctum, the private area of my grandparents’ home, the space my father called his own when has was just a boy like me. I lie on top of the bedspread and stare at the ceiling, imagining my dad’s model airplanes hanging from fishing line, the Mustangs on the tails of the Messerschmitts and the P-40s with their menacing tiger mouths taking fire from the Japanese Zeros. The closet doors hang open like the the flayed belly of a rainbow trout, its insides packed with boxes and equipment from my grandmother’s beauty parlor. I imagine my dad’s baseball cards, long fed into the fireplace but still talked about with a mix of nostalgia and reverence, hiding in a shoe box on the cluttered closet shelf. I picture his favorite records filed neatly on their wire rack: Johnny Horton’s “Battle of New Orleans” alongside Homer and Jethro’s “Kookamonga” parody; Freddie Cannon’s “Chattanooga Shoe Shine Boy;” Lee Dorsey’s “Ya Ya.” I drift to sleep, where I enjoy the fever dreams of an eight year-old boy, dreams featuring guest stars like Johnny Bench, Evel Knievel, and my dog, Moochie.

“Jimmy,” my mother shakes me awake. “Dinner’s ready, come eat.”I stand and follow her toward the piranha-infested dining room but only get as far as the bathroom. This is where I spend the rest of Thanksgiving day, projecting my body weight into my grandparents’ avocado green toilet. I don’t know how long I’m in there–ten minutes, ten hours, it’s all the same when you’re dying. My mother knocks on the door and says, “Can I get you anything?”

“Can I have a Coke?”

I hear her walk the few steps to the kitchen and ask: “Mable, do you have a Coke?”

“I knew it!” my aunt exclaims. “The little brat’s too sick to eat but not too sick for a Coke!” Maybe she has a point, I don’t know, but I do know that I passed up a steaming plate of Grandma’s mac and cheese, which is more unlikely than my granddad passing up a free Coors.

Friday morning, November 24, 1975.

I watch the tops of my grandparents’ enormous pine trees sway in the breeze, the wind rushing through their needles mimicking the sound of a distant waterfall. My father packs the last of the luggage into our station wagon’s back in the back, which presents a spatial problem given that the cargo area now holds a huge mysterious rectangle covered by the old blanket my dad packed because “you never know.” Grandpa sucks on a Raleigh while Grandma chatters nervously. “Be careful. We’re supposed to get snow and Grandpa says these station wagons don’t handle good in the snow.”

“Mable, I never said no such a goddamned thing,” Grandpa snaps.

“Oh, I know you didn’t. These are good cars.”

“We’ll call collect when we get home,” my father tells his father as the two men shake hands. “I’ll say I’m Mr. Jones so that you can decline the call.”

“Why is Dad going to say he’s Mr. Jones?” I whisper to my mother.

“Long distance calls are expensive. This way Grandma and Grandpa will know we made it home okay without anybody having to pay.” Her explanation makes no sense to me, but very little of the grown-up world does.

Back on the road, heading east to Chicago, sun in our eyes. “What’s under the blanket?” my sister asks and my parents look at each other. “What’s under the blanket?” she repeats.

“Presents,” my father mutters.

“For us?” I ask.

“Grown up presents. They’re for the guys at the plant.”

“What kind of presents?”

My dad cracks under the pressure of cross examination. “It’s Coors, cases of Coors. You don’t touch that blanket and if we get pulled over you don’t say a word no matter what the policeman asks you. As a matter of fact, promise that you won’t ever say a word to anybody.”

“Why not?”

“Because it’s illegal to run Coors to Chicago.”

“Why?”

“It’s bootlegging.”

“What’s that?”

“Get out the cookies,” he tells my mother, and she retrieves a box of chocolate chip hockey pucks that are now one week even more expired. “Everybody shut up and eat a cookie.”

We’re outlaws! I’m Snidely Whiplash, Yosemite Sam, Bobby Brady as Jesse James! This is the coolest road trip ever! I stare out the window intently, eyes peeled for Johnny Law. All across Nebraska signs alert us that police are patrolling via aircraft. My father has never seemed more clever: There’s no way those airborne cops can spot those distinctive yellow and black Coors labels hidden beneath the dirty old blanket. The man is a criminal mastermind.

Late that evening my father growls, “Goddamnit!”

My mother gasps awake. “What’s wrong?”

“Just passed a cop.”

“Is he following us?”

“I don’t know,” my father says, eyes darting between the road and the rear-view mirror.

“How fast were you going?”

“Sixty.”

“They probably won’t stop you for that.”

“You don’t know these small town speed traps. These sons of bitches will pull you over for 56.”

What will become of me when the jig is up? I’m too young to go to jail. Will I end up in a small town Iowa orphanage? Will I spend the rest of my childhood serving as unpaid farm labor? Am I doomed to the army cot beneath the piranha pit? I never should have embarked on a life of crime at the tender age of eight.

The red and blue lights of justice never flash in our mirrors; in fact, we make it all the way back home to Chicago without incident. Bootlegging turns out to be a pretty boring crime.

A year and a half later Smokey and the Bandit hits the theaters. Sure, some of the facts have been changed for dramatic effect, but the big rigs, the Coors, the miles of highway–my family’s criminal exploits have been fictionalized. Fortunately, the filmmakers left out my explosive diarrhea.

Clearly somebody talked, but not I. And as much as I want to brag on the playground that my family ran Coors from Colorado to Chicago while evading the long arm of Buford T. Justice, I never do. A promise sealed with a petrified cookie is a very solemn thing.

Leave a comment